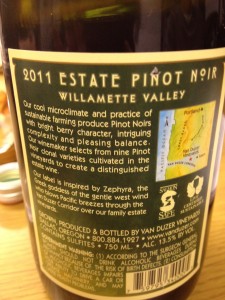

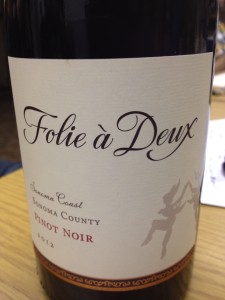

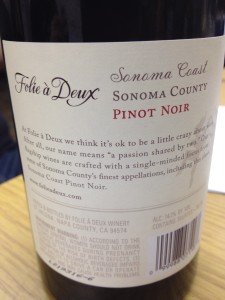

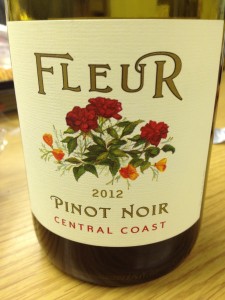

So last last Friday, the 16th, member Kyle Bieneman held a wine tasting class on Pinot Noir. I’ve been meaning to get this post up earlier, but enjoy the pictures and information from the handout:

“It’s…thin-skinned, temperamental, ripens early. It’s, you know, it’s not a survivor like Cabernet, which can just grow anywhere and uh, thrive even when it’s neglected. No, Pinot needs constant care and attention. You know? And in fact it can only grow in these really specific, little, tucked away corners of the world. And, and only the most patient and nurturing of growers can do it, really. Only somebody who really takes the time to understand Pinot’s potential can then coax it into its fullest expression. Then, I mean, oh its flavors, they’re just the most haunting and brilliant and thrilling and subtle and…ancient on the planet.” –Miles Raymond, Sideways

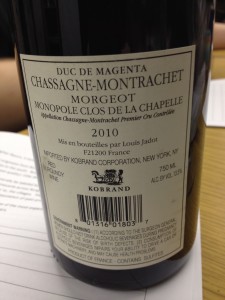

Note: From Burgundy

The grape: Pinot Noir grows in tightly packed bunches (the “Pinot” in the name refers to the pinecone shape of the bunches). These tight bunches tend to be somewhat more susceptible to disease. Being thin-skinned, the grape is also at great risk from extremes in temperature. Fortunately, as it ripens early, it can be grown in cooler regions than heartier grapes (like Cabernet Sauvignon).

Color: For red wines, color comes from the skins (it is not naturally present in the juice) in a process called “extraction.” Grapes go through a machine called a “crusher-destemmer,” and rather than being juiced as with white wine, the pulpy mass is then fermented in giant vats. Note that the skins will naturally float to the top, forming a “cap,” requiring some kind of system to circulate the fermenting juice (whether a “punch-down,” a “pump-over,” or some sort of a mixer).

Sometime after fermentation has completed, the “free run” is drained off. The remaining “pomace” is then pressed to extract all the remaining liquid. The free liquid is generally light in flavor and color than the pressed liquid, and so will often be aged separately, being blended only at the end to fine-tune before bottling.

Pinot Noir is thin-skinned with less color (anthocyanin) in the skins, it tends to extract less color, and thus is paler than most red wines. Being lighter in flavor, some winemakers will even leave the stems in for fermentation to impart more “tannins.”

Tannins: Tannins are much more present in red wine than white wine, partly because they come from the skins during extraction (as well as seeds and stems, if present), and the oak barrels during aging. Tannins are traditionally used to turn hides into leather (“tanning”), hence the name. This is why bitter red wines often make your tongue feel dry and leathery. The “resolving” of tannins is a prime reason why many red wines get better with age.

Pinor Noir is notably low in tannins, and so some winemakers will leave the stems in for fermentation.

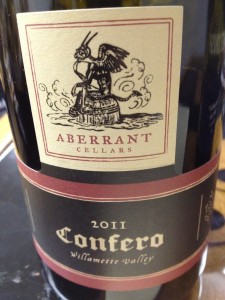

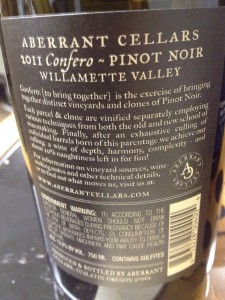

Note: Australian

Flavors in Pinot Noir: As a lighter, more delicate wine, flavors tend toward the redder fruits such as cherry, strawberry, and raspberry. Less prominent notes might include vegetal (beets, green tomatoes, olives) or earthy (truffles, barnyard) flavors. Pinot does not typically display the darker fruit (plum) or spicier notes (cigar box) of other red wines. As a result of its lighter flavors, it tends to pair well with pork and fowl, rather than beef.

Burgundy: Pinot Noir originates from Burgundy, a region in the east of France, between Champagne to the north, and Beaujolais to the south. Burgundy is divided into four major sub-regions (from north to south, and highest to lowest quality): Cote de Nuits, Cote de Beaune, Cote Chalonnaise, and Maconnais.

However, Burgundies will generally be labeled by their village, of which there are too many to list. There are about 600 “Premier Cru” vineyards across Burgundy, and only 32 “Grand Crus,” which will be more expensive, and generally superior to, the villages. The Premier and Grand Crus are designated by the French government based on the reputation of past production.

The Grand Cru red Burgundies are some of the most expensive and sought-after wines in the world, costing nearly $1000 a bottle in good years.

Thanks again to Kyle for these notes.